Frames of Thought – Unifying Good and Evil

What Merging Mind and Matter Makes Possible

Frames of Thought: Fourteen

The Frames of Thought series of essays offers a scene-by-scene glimpse into my thoughts, motivations, hopes, backstories, struggles, and anything else that comes to mind as I create this animation.

Script Extract

We’re talking about finally bringing together the world of matter and the world of mind into one grand, unified, all-inclusive reality—because, apparently, they were separate all this time? Who knew?

The Scene

There are about 7,000 languages spoken around the world. That’s right—7,000 different ways for people to misunderstand each other. And just to keep things interesting, we’ve thrown in a few non-verbal forms too—like sign language, programming languages, and that glorious human invention where you prove things with symbols: mathematics.

Each language we use grants access to a different mode of knowing. Mathematics is a language that provides us with a precise and reliable way to understand and describe the structure of reality. This understanding enables us to act effectively by allowing us to predict outcomes, solve problems, develop tools, and make sense of our experiences.

Mathematics is fantastic at describing the outer shell of reality—the measurable stuff. You know, the parts you can poke, weigh, count, and put on a chart. If it can be formalised, repeated, or generalised, maths is all over it.

But when it comes to the inside—the mysterious, weird, deeply human stuff like feeling, meaning, or what it's like to fall in love or stub your toe at 3 a.m.—maths just sort of shrugs and backs slowly out of the room. Try plugging heartache into an equation and see what comes out. Probably a syntax error.

At best, maths gives you the shadow of inner experience. It can map the tendencies, sketch the outlines, and maybe chart your dopamine levels on a Monday morning—but it doesn’t feel the Monday. It doesn’t know what it’s like to be you, staring into a coffee cup, wondering if the universe is just a badly coded simulation. Maths can’t touch that. That’s soul territory.

So yes, maths might be the language of the universe—but it’s got no vocabulary for longing, no formula for meaning. It tells you how things work, but not why it matters that they do.

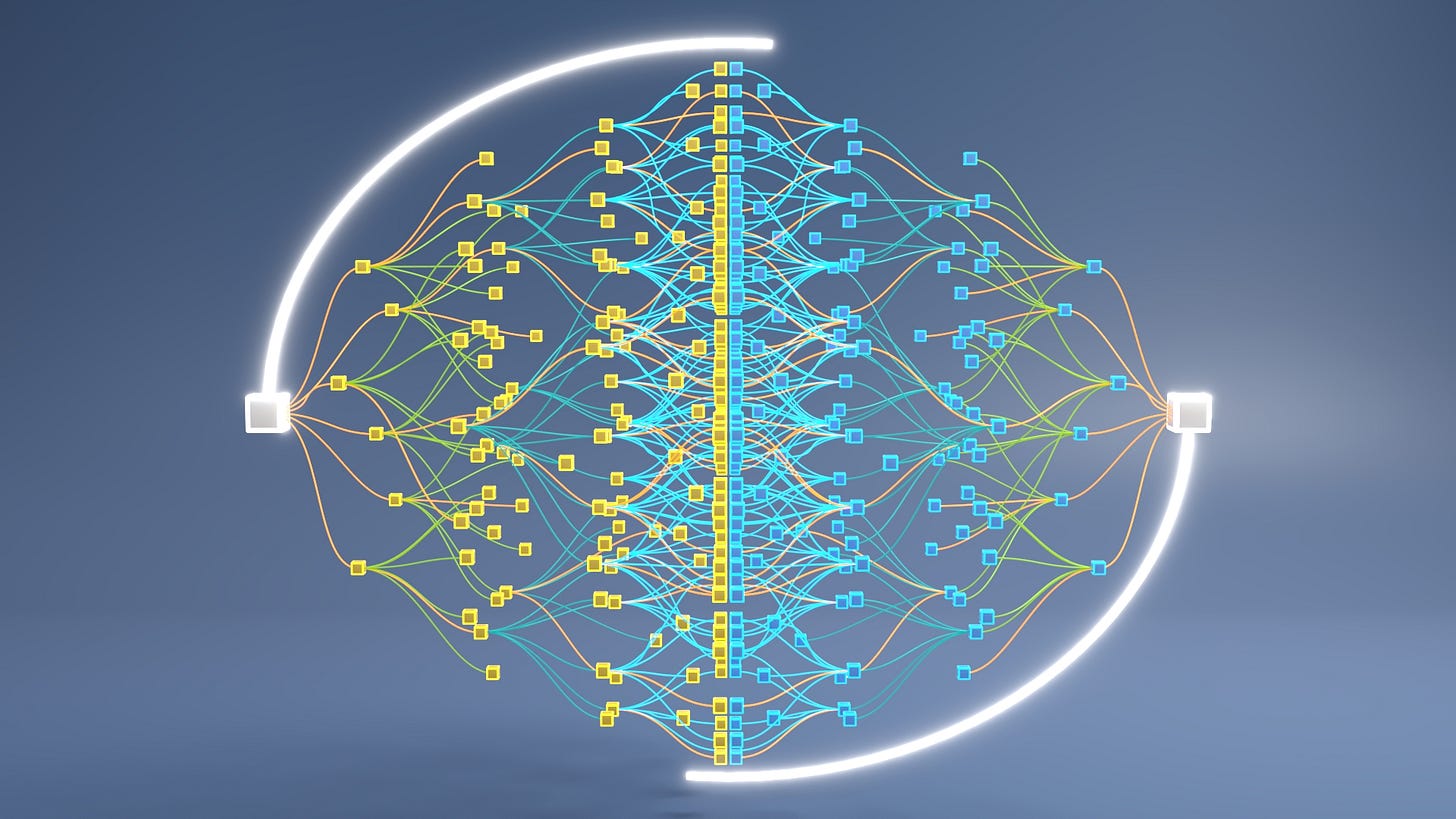

And yet, mind and matter are part of the same reality. So, to bring the world of matter and the world of mind into one grand, unified, all-inclusive understanding, we need a language that can describe both. We need a language that can reliably help us understand and describe the structure of mind as well as spacetime, forces and matter.

The artist uses a pre-verbal, intuitive language underpinned by the sense of things: the sense of form, flow, proportion, and presence. Creativity for the artist is about sensing how forms relate in space, about feeling rhythm, pacing, tension, and release, about grasping wholes and patterns intuitively, and a “rightness” sensed before it’s reasoned. It's not a formal language. It is a felt grammar of being. You don’t learn it by definition; you learn it by doing—by noticing. In a sense, it's the root of all languages—a pre-conceptual feel for how things hold together, move, and carry meaning—beneath both words and numbers.

It took me over twenty-five years to turn that pre-verbal, intuitive language—the language of consciousness—into a formal language. I had to learn to think logically in that language, keeping the spoken language out of the loop. Eventually, I managed to tease out its elements, syntax (rules), lexicon, semantics and inference rules. Together, these elements create a closed system where meaning and truth arise internally from structure and rules—not from blind intuition, perception, or experience.

The Artist That Wasn’t an Artist

My journey to uncovering the language of consciousness was a strange one. My first year of studying graphic design was a total mystery to me. I didn’t know what was going on. The only thing that made sense was geometric drawing, as it involved logic. It wasn’t that my mind wasn’t making use of this hidden language. The intuitive language is the native language of all minds. It was just that it was all happening behind the scenes, which is mostly the case anyway. The problem for me as an art student was that I wasn’t attuned to it. So I felt like an impostor. My mind was producing art, and I didn’t know how it did it. I had no sense of what constituted good art and what did not. The only measure of quality (whatever that word meant) was the marks I got. The fact that I was actually doing quite well, all things considered, made it all even more baffling.

One day, in an abstract painting class, I was sitting there watching my classmates make nonsensical brushstrokes on their canvases. My own canvas displayed an equally absurd disarray of coloured confusion. My lecturer, Gunter van der Riese, a well-known South African artist born in Germany, came over to assess my attempt at transferring paint onto canvas. I told him this was making absolutely no sense to me—not even a bit.

On the floor was a piece of paper on which I had cleaned my brush. He asked me if I’d made those ‘brushstrokes’. I had. He then said I should stick it on the wall and look at it every day until I ‘got’ why it was good.

Eventually, I ‘got’ it. The lightbulb switched on. By the end of my second year, I had won the Student of the Year award. By the third year, I was undertaking projects that were far beyond the curriculum, including constructing a spaceship that had landed on Mars and a spacesuit for a TV commercial shoot.

In my first job interview at Collin Bridgeford Studios, I was told I couldn’t work there because I’d get frustrated by not being able to do creative enough projects.

This experience of being an impostor in the art scene was very formative. I was observing my mind from a third-person perspective, doing things that made no sense. Then, I uncovered its hidden language. Even though I didn’t understand it in any precise way, it was … Wow!

This detachment caused me to see the creative process not as an identity—me, the artist—but as a kind of mechanism. It was a process I could now sense but still didn’t understand. The logical next step was to attempt to decode it.

What Does the Uncovered Language Offer Us?

To decode intuition as a complex language—capable of describing both mind and matter through a unified grammar—might at first suggest that we are now free from the tyranny of dualities. It might indicate that the subjective, with its feelings and emotions, and the objective, with its deterministic flow of events, can now be blended together—smoothed out—until there is just a homogeneous oneness. But this is not the case at all. Instead, we realise that there is a single canvas onto which we project the myriad dualities of life. It gives us a way to understand them not as forced upon us or mere illusions but as functional distinctions—provisional lines we draw on an underlying unity.

The mind, in this light, is not supernatural. In fact, there is no evidence to suggest that anything is supernatural. The mind is constructed by the material brain, not from particles but from the elements of this uncovered language. It is an information construct, a matrix of non-material elements, relations, and associations assembled together. Through this, causation flows from matter to mind and back into matter. It is one flow system.

We then demarcate segments of this unified flow and call them good and evil, me and them, love and hate, right and wrong, success and failure, life and death. These projections on the unified flow are important for life to function. We have to have a sense of self, of right and wrong. However, by understanding the oneness of mind and matter, we can gain more control over how we set and use those boundaries.

This is not a form of relativism, where truth, morality, or meaning is not absolute but depends on context. Not at all. By bringing mind and matter together within a single framework of understanding—weaving identity, emotions, intelligence, hope, faith, and love into the mechanics of matter—we uncover a pattern in that flow that points to a profound meaning and purpose of life. And it is this meaning and purpose that forms the basis for a robust moral and ethical framework. Not one imposed on us from outside by some supernatural authority, but one that emerges from the nature of reality itself. At the core of our reality lies a simple principle—a principle that transforms chaos into order and gives birth to life and the universe. I call it the Principle of Entropic Stability, but it has a much more accessible name: love.

Next Up

In the following essay, we shall revisit Plato’s Cave to explore why the transition from a dualistic framework to a monistic one may prove nearly impossible for some individuals—and what might be done to address this difficulty.

Thank you.